Look at early Maryland and Virginia quilts, and regional similarities emerge. Some designs were popular outside this region; others were very local. Designs migrated with their makers: European traditions came to America, and American-born quilters moving West brought their designs to influence quilting in new territories.

The quilts which survive display elegance and skill, disproving the old myth that quilting arose from dire necessity. These quiltmakers had leisure time, sewing for pleasure and to show their refinement and their eye for elegance.

The prevalence of the iconic “quilting bee” is overstated by sentimental myth, but quiltmaking could indeed be a shared activity. Though quilts are credited to, and probably mostly made by, one maker, we can assume some help from family members, servants enslaved and free, and neighboring relatives and friends. We are fortunate to know the origins of most of our quilts, and can largely reconstruct the household to speculate who else may have lent a hand.

Artists loved depicting “quilting parties” or “quiltings” (later often called “quilting bees”) in which men joined the quilters to socialize. But often, quieter quilting prevailed, with servants, family members, neighbors dropping by, or out-of-town house guests sharing in the stitching of the quilt top to its filling and backing. Detail from “A Quilting Party in Western Virginia,” artist unknown, published in Gleason’s Pictorial, 1854.

Detail from the Tree of Life and Birds Quilt made by Catherine "Caty" Parker Custis (1753-1840); Gift of Mr. and Mrs. James R. Kappler; Conservation adopted by Massachusetts DAR.

A desire to achieve and display “refinement” was part of middleclass American women’s culture. The quilts in this exhibition come from homes which would have had other elegant furnishings reflecting their owners’ means and taste.

Imagine these quilts as bedcoverings in tasteful and comfortable interiors.

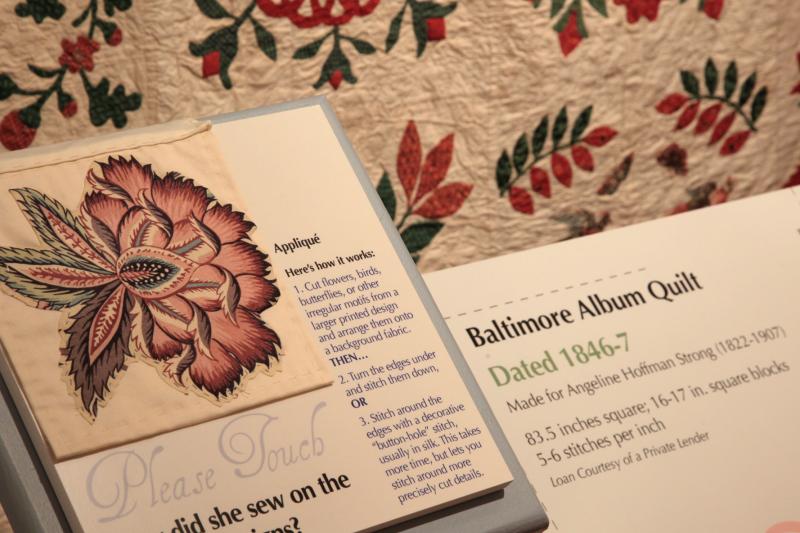

By the 1840s, American factories were producing miles of printed cotton fabrics as fine as English imports. Small-scale calico designs became popular and were widely affordable. While New England is famed for its textile mills, Maryland had many cotton factories, some producing calicoes. Maryland and Virginia quilters thus had a vast selection of colorful fabrics to choose from for their album and other quilts.

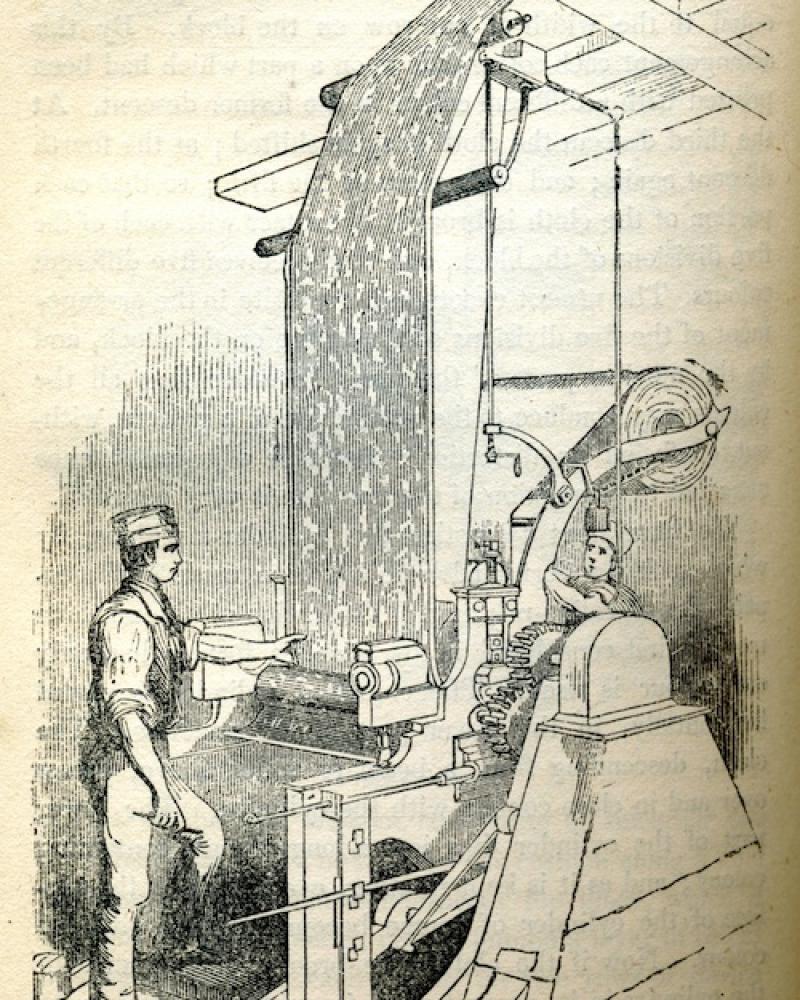

Roller or cylinder printing, introduced at the end of the 1700s, fed fabric through the printing machine. Each cylinder or roller applied one color of the printed design. “Cylinder-printing,” from British Manufactures by George Dodd, 1844.

Rural and small-town quilters had access to the trending items of each season, just like city dwellers. Merchants in communities far from cities, where many of these quilts were made, knew that their customers were aware of, and wanted, the latest fads. Shop owners traveled often to Philadelphia or Baltimore for the latest in fabric and other goods, returning to advertise them to their customers.

Detail from “Messrs Harding Howell & Co.,” Ackermann’s Repository of the Arts, 1809, Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University. Reproduction cotton dress and accessories in the style of c.1810.

Fabric Dyeing and Printing

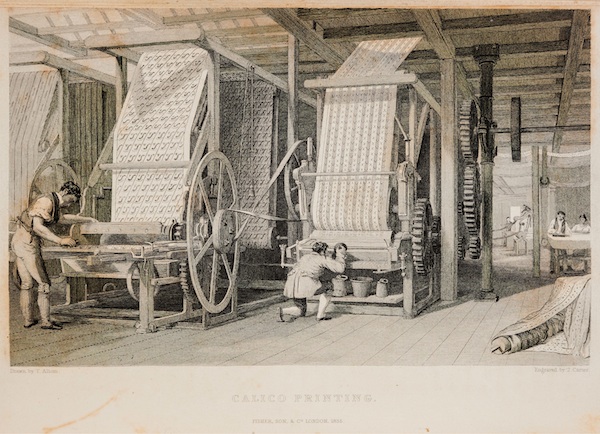

The quilts displayed in Eye On Elegance contain many fabrics made with the latest technologies, which would have been appreciated by maker, user and viewer. The 1800s saw many innovations in fabric weaving, dyeing, and printing. Chemists experimented with recipes for new colors and dye effects, and textile machinery was at the heart of the Industrial Revolution. Machine-made and machine-printed fabrics rolled off looms more quickly than hand-woven and hand-printed ones, making more fabric affordable to more people. By 1850, block printing, though possible to achieve with machinery, had mostly been replaced by roller-printing.

In the early 1800s, roller-printing could produce only small prints in just a few colors, but by mid-century, as technology improved, complex large-scale patterns could be printed. Roller-printing machines, 1830s. Engraving by J. Carter from drawing by T. Allom, published in Edward Baines’s History of The Cotton Manufacture in Britain (1835).

Large cylinders printing fabric by machine sped production enormously, bringing costs down and making colorful printed cottons affordable to nearly everyone. Roller-printing cylinder, 19th century, loan courtesy Debby Cooney; Wooden and wood-and-tin printing blocks, DAR Museum, gift of Kathryn Berenson.

.jpg)